Make Electricity Cheap Again - part 1.

We succeeded in making "Electrify Everything" an idea. We failed to make electricity cheap. Lets make electricity cheap again.

This post is mostly addressed to my American friends. Right now the US climate movement is licking its wounds about what from the IRA was lost in the “Big Beautiful Bill”. I think better questions are about what was wrong with the IRA? what can be done going forward ? Much of this stems from my concern that we’ll never solve climate change for moral reasons, but need to make the economics work, everywhere for everyone. That is a project of making electricity very very cheap.

The IRA was classically regressive policy. It wasn’t polite to say it at the time because everyone was celebrating getting ANY big climate policy done, but due to political circumstance it amounted to tax deductions for people who could for the most part already afford the nice things required to decarbonize.

And because the climate movement and policy writing sector is over-populated with masters degrees in sustainability, not electrical engineering degrees in power electronics and experience in manufacturing, it had too much detail on social policy, and not enough detail on how to make the electrification kit actually cheaper, and the electricity that feeds it cheaper again.

That sounds very critical but I’ll stand by it, because I can see how this decarbonization through electrification thing can work. Australian energy and climate politics aren’t as ruinous as America’s because we have cheap rooftop solar, cheap installation of heat pumps and induction stoves, and reasonable and maybe improving grid and electricity market regulation and policies. The economics are described well in “The Big Switch”, and even better detailed at household level in “Plug-In”.

With cheap electricity, and the efficiency of electric machines combined, you can make the whole economy more productive, and save every household thousands and business millions and nation billions. So lets focus on cheap electricity.

How do we make electricity cheaper in the US ?

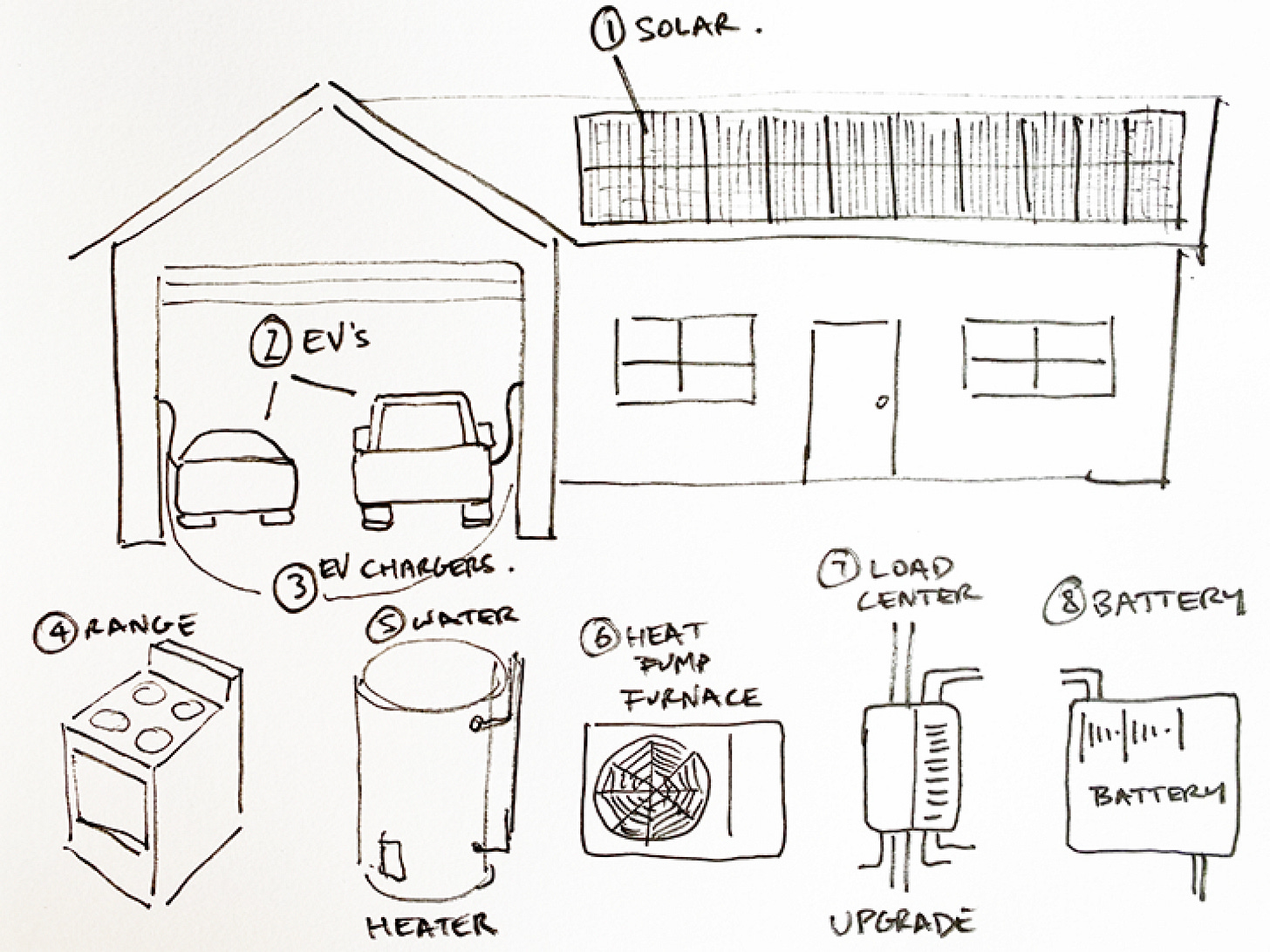

Get as much electricity as you can from local solar. This has two components…

Make rooftop solar the cheapest form of energy anywhere and do as much as possible.

Get as much as you can from local commercial and public-space solar that is within the “community”

Utilize the wires better. Local distribution grids are frequently the most expensive component of electricity.

Make nuclear energy cheaper.

Make connection cheaper and smash the monopoly utility.

(I thought I was going to put all of these in one post, but given how long (1) is, I’m going to break it into 3 or 4 parts).

Lets look at these one at a time, and their potential to lower the price of electricity, but before we do that, lets look at the price of electricity and why it matters for electrification.

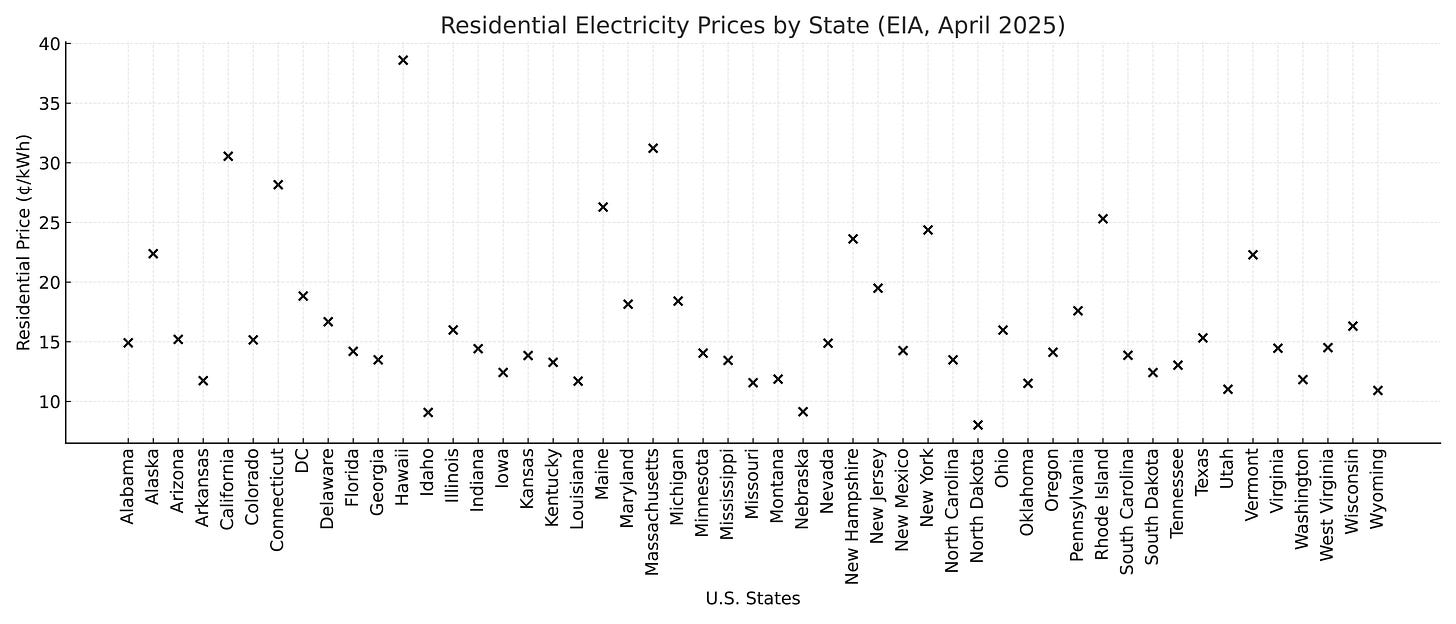

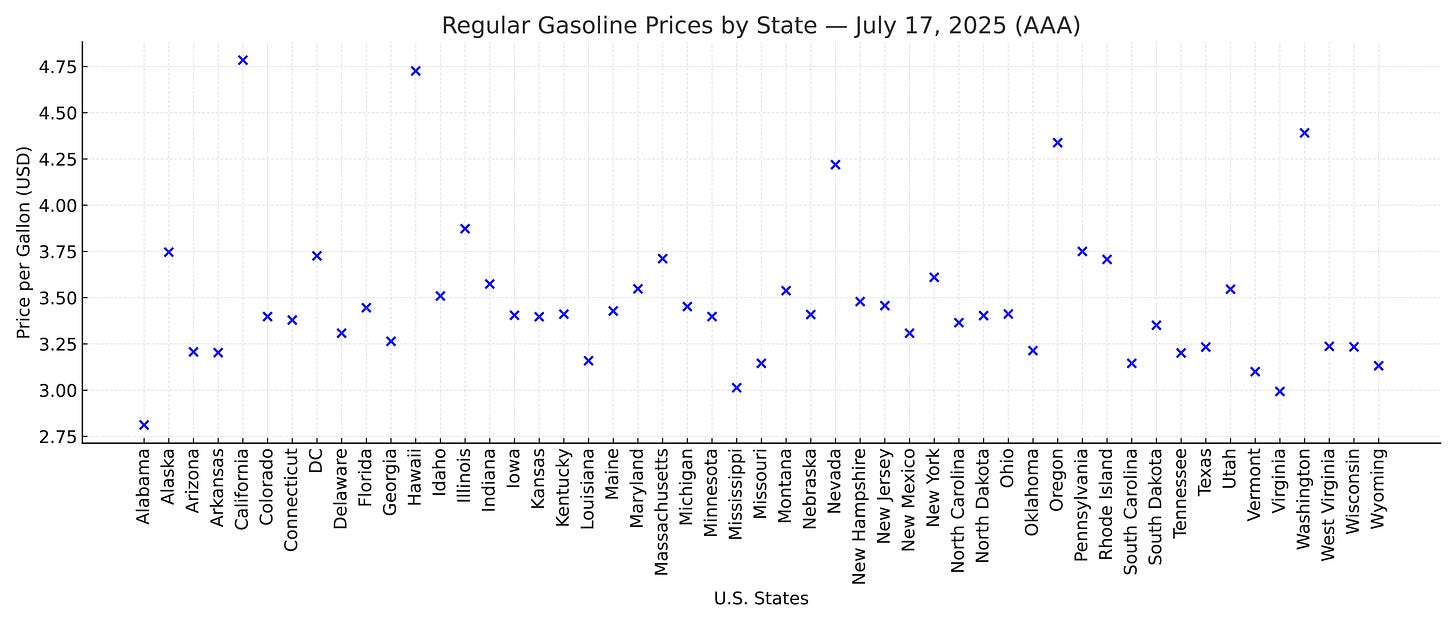

The retail price of electricity as delivered to a residential customer varies greatly in the US. From under 10c/kWh in Idaho, North Dakota, and Nebraska to above 30c/kWh in California, Hawaii, and Massachusetts. There are a lot of reasons underlying the price differences and hold those criticisms for a minute.

The reason you care about making electricity cheap isn’t so much about cheap electricity, but about making the economics of an electric car just way better than a gasoline car (or heat pump or etc.). Above are the prices of regular gasoline by state in the US. Also for July. The closer you are to Texas, Alabama or Louisiana, the more likely you are to get gas for under $3 per gallon. California and Hawaii again feature at the high end of the price landscape at $4.75 per gallon.

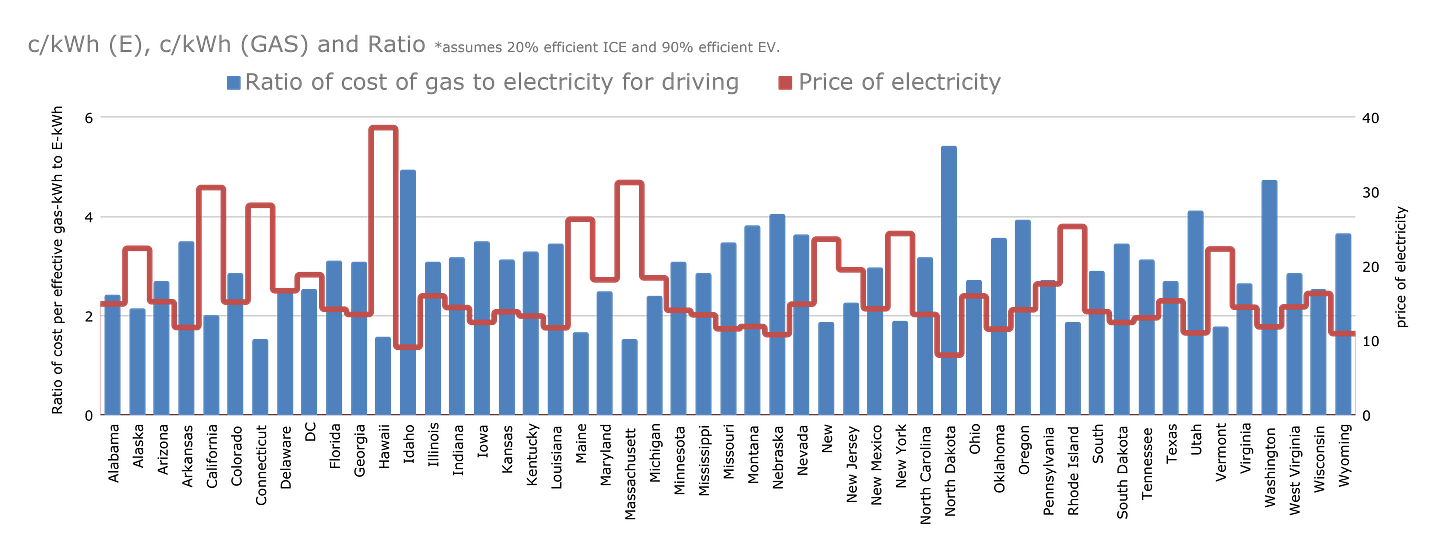

Now we can compare the costs of driving in one graph, and it tells you something important about electricity - you have to make it cheap.

The blue bars are the ratio of the cost of driving a gasoline car relative to an electric vehicle. The taller the bar, the more (relatively expensive) it is to drive with gasoline. In Idaho it is 5-6 times more expensive to drive with gas, or 1/5th the cost to drive the same mile with electricity. This isn’t due to expensive gas, this is due to cheap electricity. The red line shows the price of electricity in each state in c/kWh. Cheap electricity makes the driving so much cheaper than gasoline cars that it is compelling enough to consider the higher up front cost of EVs. Of course China is changing that equation by making EVs very cheap. This is the modern Australian experience. We pay EVEN more for gasoline (petrol) than Americans, because we are far away and don’t have our own oil reserves, and we pay LESS for electricity for reasons we will see soon, so driving an EV is a SLAM DUNK economically, and its mostly only culture, misinformation, lethargy, inertia, and fear of debt that keeps us from driving the cheaper-to-operate EVs.

This was the promise that Sam Calisch and I modelled and outlined when we were writing chapters on household electrification economics for the book Electrify. We modelled a hypothetical USA with rooftop solar at US$1/Watt installed cost, and everyone saved money on electrification of everything because it made the solar generated portion of their electricity cheaper - like 6-7c/kWh after financing. Australia now routinely installs solar at $0.55 per watt. I am personally installing a 15kW system on my garage at $0.45 per watt (bigger systems are cheaper!). That is a financed cost of electricity of (US)2-3c/kWh. If your electric truck in idaho were running off australian rooftop solar, those miles would cost 1/10th of what it costs to drive with gasoline. Who isn’t going to sign up for a subscription to driving (electrically) at a 90% discount to the gasoline subscription ?

So, how do we make rooftop solar cheap? - First the numbers.

Energysage does a good job documenting state by state installed cost in the US. https://www.energysage.com/local-data/solar-panel-cost/

SolarChoice does a good job of documenting the installed cost in Australia.

https://www.solarchoice.net.au/solar-panels/solar-power-system-prices/

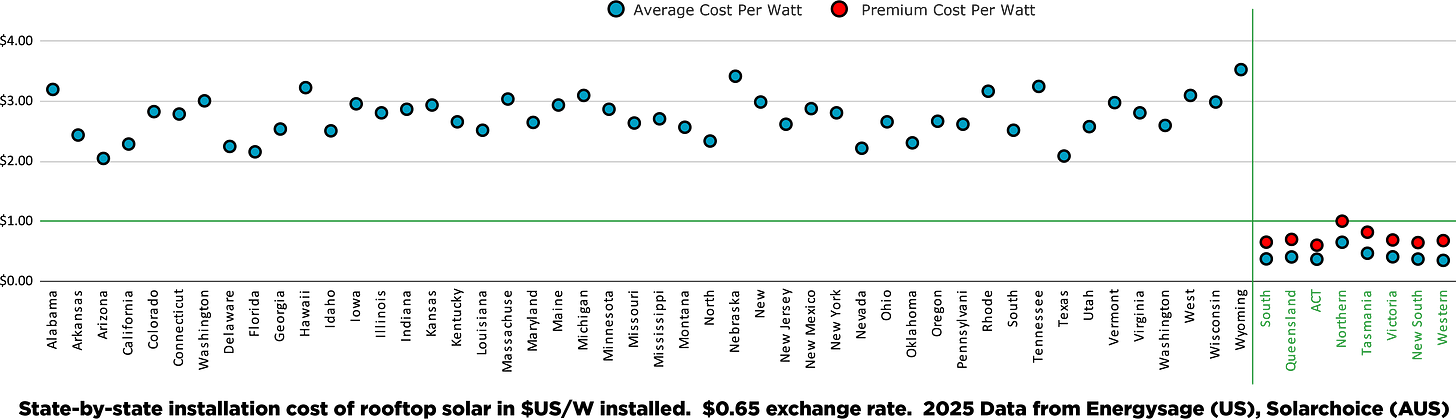

You can naively apply the exchange rate and compare both countries, state-by-state. There is still a tiny rebate in Australia (phasing out in 2030 as per the plan). But that does not explain the gaping chasm… Even the premium stuff is under $US1/Watt. The mid-market product is as low as $US0.50/Watt. From these numbers the US average price is $2.74 per watt and the Australian is $0.43. The modules themselves are about $0.10 per Watt (pre-tariffs). Australian installation labor is similarly priced to that in the US. The difference is soft costs - cost of sale, cost of inspections, cost of overhead, cost of permits, cost of liability and insurance.

If free fusion energy magically apperared tomorrow it could not deliver electricity to your house cheaper than the current (and still falling) price of rooftop solar (in Australia).

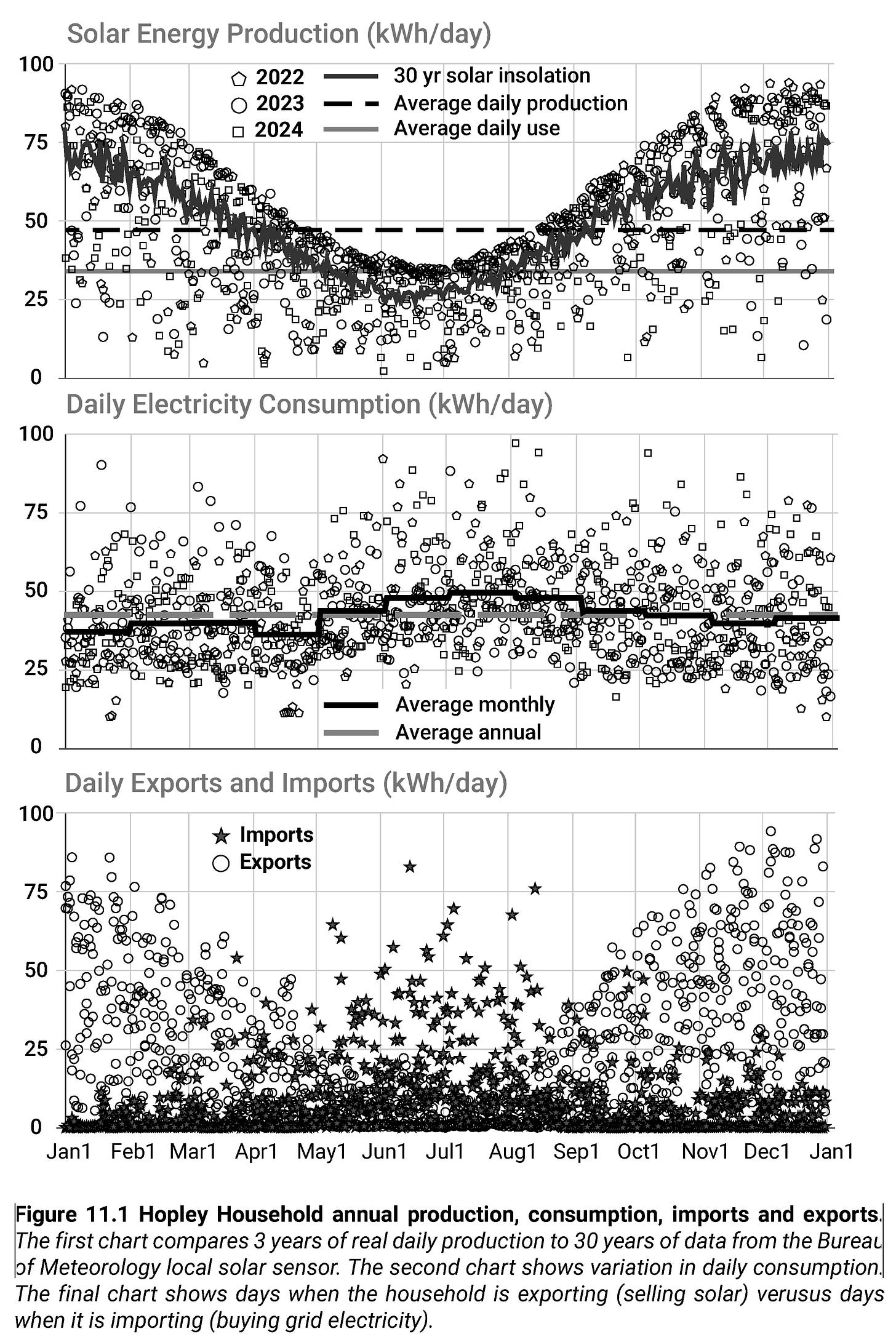

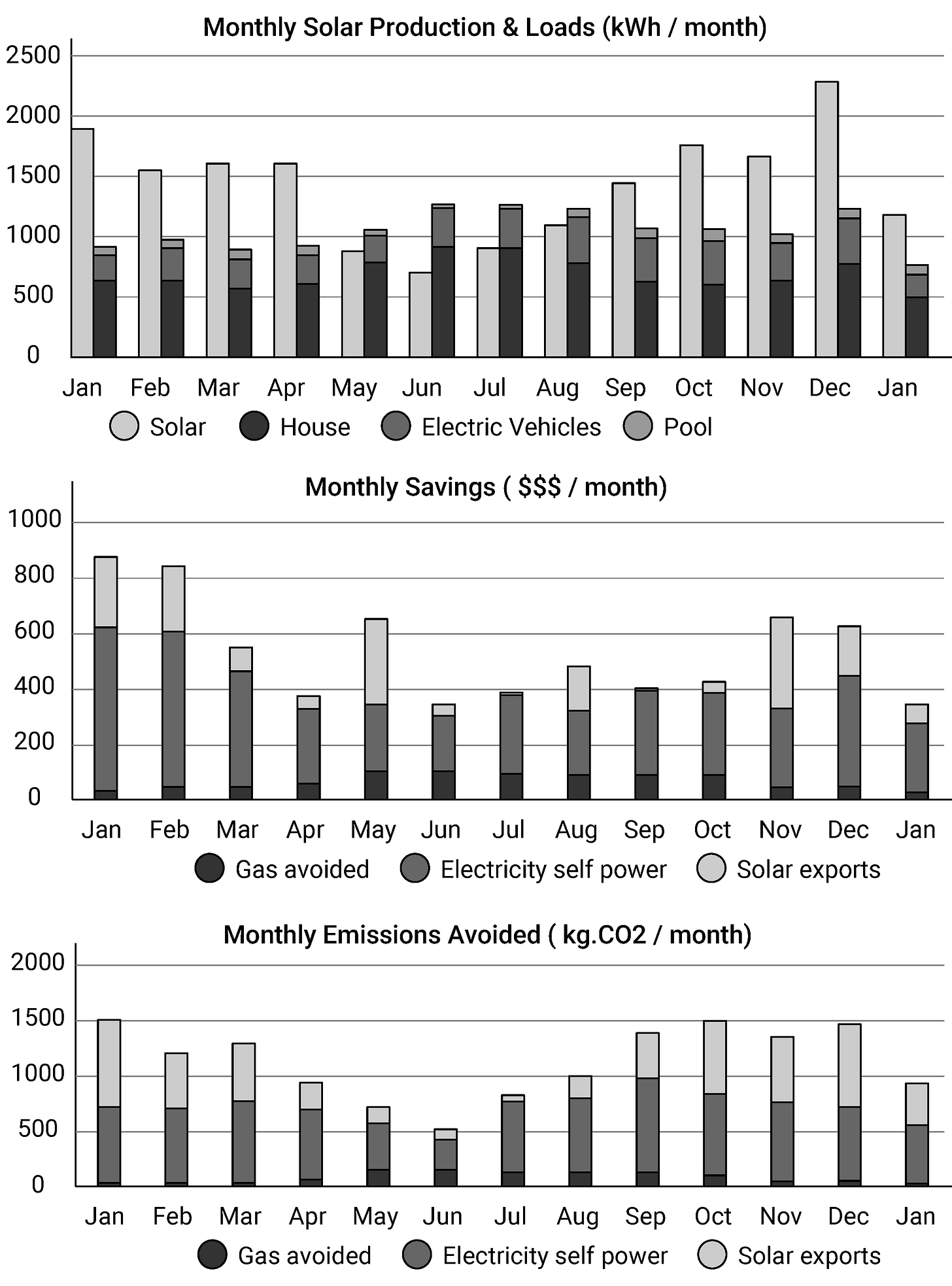

Because it is so cheap in Australia, people install a lot of solar. Our rooftops generate over 10% of total energy supply. For an individual household with a large rooftop, it pays to install more than you need. My friend Fred’s house produces 141% of the electricity it needs in a year to run an entirely electric life including 2 cars and a heated pool. This is achieved with a 15kW systems. This is true abundance.

Using data from a local government sensor Fred was able to design his system to generate more than his projected energy demand all year round (first part of figure). His total energy cost is mildly higher in the winter months, as would be expected, but the over-capacity or abundance compensates (second part). The third graph is very important. This shows days Fred is an exporter (making more energy than he uses) and days the house is an importer (using more than they produce). For 9 months of the year they are for more often exporters than importers. For 3 months they rely on the larger grid to deliver wind power and other renewables. It should be emphasized this is one of the reasons it is never really sensible to think “off grid” when you think rooftop solar, but thinking “grid augmentation”, or cheaper than grid.

The next graph below shows it well. (A) compares generation to total of major loads through the year. (B) Dollars saved. (C) Emissions avoided. Fred makes more energy than he needs and the spillover can be used by his neighbours. He is saving around AUS$8000 per year (~US$5000). He is bascially zero emissions. At least 100 million americans could be experiencing this abundance. Another 100 million could reap half of this reward.

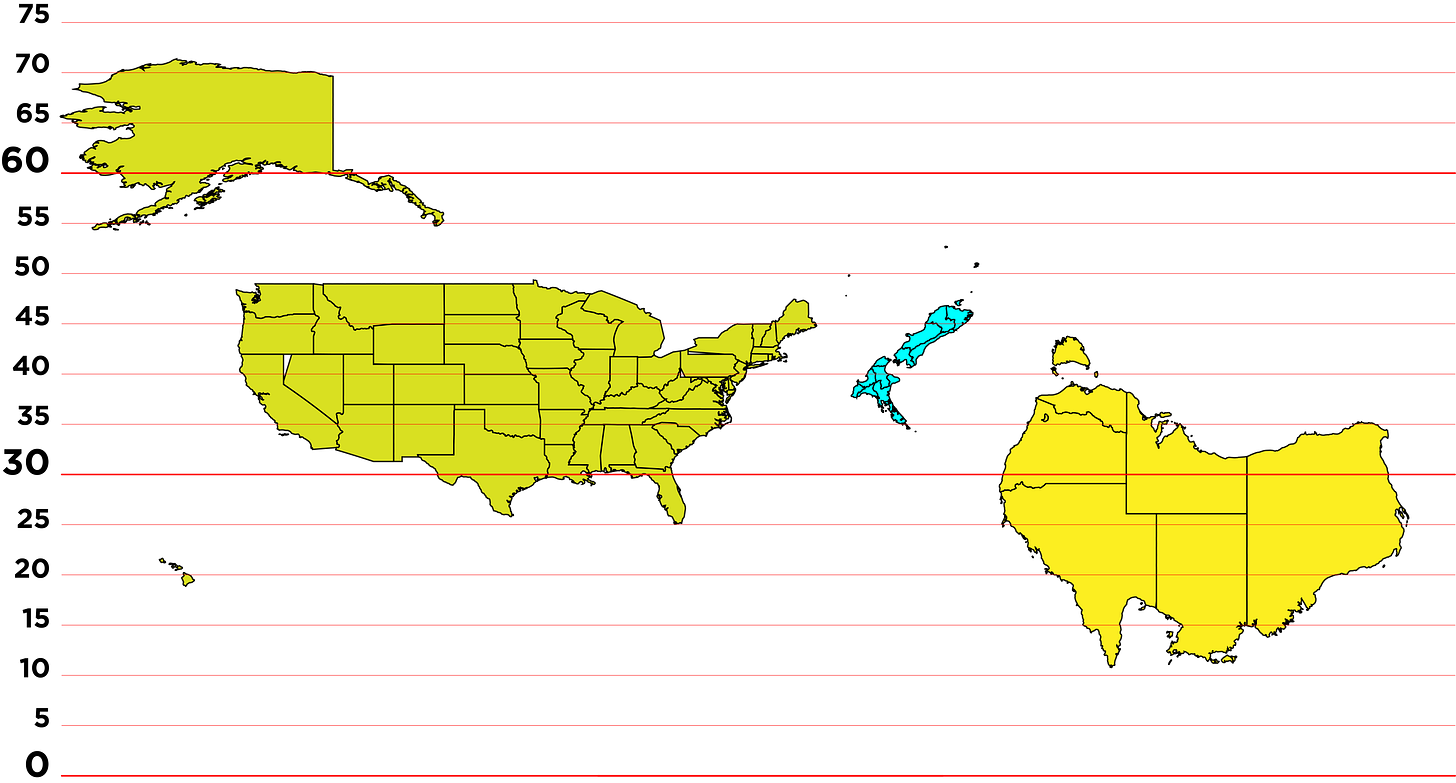

This is not because Australia is “sunnier”. Fred lives in Sydney, at about 34 degrees of latitude. His household story can be true pretty much anywhere up to about 38 degrees of latitude, or pick a line from northern california to virginia. I’m adding a dumb map of the world for people to laugh at. I threw in New Zealand because they are cool, and are currently contemplating and implementing world leading distribution grid market rules which will unleash rooftop solar.

America’s rooftop solar potential is huge, as outlined by NREL in this paper. The paper is old now. It assumed 16% average solar cell efficiency. Routinely you can get 22-24% efficient modules now. To be clear, the cheapest energy system of any kind that the USA could deploy involves as much rooftop solar as possible. As we’ll see shortly, proximity is key. This solar delivers energy behind the meter, with no transportation and distribution costs.

Why the 6-7X difference in cost between the US ?

Permitting costs.

Liability costs.

Inspection and truck-rolls.

Solar industry optimization.

Cost of sale.

Tariffs.

Andrew “Birchy” Birch talks about this a lot and has been a good agent in making the US aware of this missed opportunity, and even working on digital tools to lower permitting costs with SolarApp+.

I go further than Birchy and think it can be even cheaper, and there are some un-appreciated pathways to truly cheap rooftop solar.

Permitting : A permit in Australia can be had in 24 hours using an app on your phone. The tradesperson can do it for you. This means you can make the decision to buy solar and be installing next day. In the US the average delay is closer to 60-90 days. People get cold feet in that time. This is probably worth 50c of the cost in the US, but is actually more as it also increases the cost of sale. Part of the problem in the US is that permitting is local, and there aren’t national rules, in fact their are 10,000 AHJs (Authorities Having Jurisdiction) that make it hard. Thats a lot of law to navigate.

Liability : I think it is under-appreciated how much liability contributes to the cost in the US. In Australia the government and industry created a certification process by which installers get trained to a minimum quality and safety standard. This eliminates a bunch of liability that would otherwise be held by the contractor. The certification and training process also contributes to workforce development. It is hard to pin a number on what this adds to US solar costs, but I’m going to guesstimate it at 25-50c/W.

Inspection and truck-rolls. : Because Australia certifies installers to a quality standard they can choose a lower cost way of guaranteeing quality. We also do not require as many inspections. In the US, depending on where you live, there might be as many as 3 inspections required to install your solar: a pre inspection, an electrical inspection, a post-job inspection. Rolling trucks costs money. Inspections roll trucks (and delay other trucks). With workforce certification you only need to do random statistical numbers of inspections. More when the installer is young and learning, less later as they develop a quality reputation.

Industry optimization : In Australia the supply chain is remarkably flat. Some installers even purchase modules direct from China at wholesale prices. Some from a wholesale distributor. The US has more layers of supply chain with lower scale and higher margin. I believe this adds another 25c to the cost.

Cost of sale : The cost of sale is probably 1-2c/kWh. These things sell themselves over back fences as neighbours extoll to other neighbours the cost savings. In the US I saw data a few years ago for SUNRUN that pegged cost of sale at close to US70c/kWh. If a product is more expensive than the incumbent, the sale is expensive because its a luxury good. Lower the first few components of the cost of solar in the US and the cost of sale will give you a further huge discount. It is crazy to contemplate that Australian rooftop solar installs for less than the cost of advertising solar in the US.

Tariffs : I don’t think tariffs are a good idea, especially when we need to move quickly on climate action. But even if you have tariffs of 100% in the US on Chinese solar modules it would only add US$0.10 to the price. Its the smallest cost component in this list. It is hard to avoid Chinese solar as they are ~80% of global production, but hopefully this post makes clear that the majority of the money in solar is in the installation and financing. Given it saves the country more money than it costs to make them, solar can be a win-win, irregardless of where it is made. I do not know why it has become bipartisan consensus in America that everything chinese is bad. Chinese rooftop solar can be good for all parties, and the climate.

The most impactful way to make US electricity cheap again is to maximize the amount of rooftop solar. This is key to unlocking household savings, as cheap solar amplifies the efficiency of electric machines in your life, and their economic advantage over fossil machines. There isn’t a single pathway, but rather the cost is caused by overlapping problems.

More on making electricity cheaper by using more community energy, utliizing the wires better, making nuclear energy cheap again, and changing the relationship with our utilities in posts coming soon…

I’ve worked in PV and ESS industry in the US for almost 18 years. I’ve been in the field or in project management roles for projects of all types, all over the country. At one point, in fact, I worked for an Australian company, CBD Energy, that was trying to establish a residential installation business in the US.

The kind of critique you’re making is easy to formulate at a high, rather abstract level, but it’s not helpful at all to spur any real reforms without more specifics. From reading this, I don’t think you’ve spent much time talking to people who actually work on the operations of a developer or installer here, or know much about how the construction industry works here.

A few points of feedback from someone who has:

1) The US is a HUGE country, and we have a long tradition of state and local control over construction work. There isn’t a simple institutional mechanism for nationalizing permitting bureaucracy and construction oversight in local construction, and the scale of attempting something like that is far harder than it would be in Australia, which has a much smaller population and a more centralized government. So any attempt at reform needs to work within existing institutional structures, not imaginary ones plucked from countries that have a different history, geography, demography, etc. I’m not convinced either that a nationalized process would be any more efficient. The US government is good at sending out checks and doing large projects; for good reasons, local implementation is usually left to states, counties, cities, even for national programs, like Medicaid. If permitting remains local, that means that it has be managed and reformed locally.

2) Building construction is radically varied across the US, particularly for residential and smaller commercial buildings. Some areas, like southern CA and AZ, have lots of low-pitched shingled roofed, single story houses and low-profile commercial buildings with outdoor services. These are comparable with Australian building stock and are easy to install on. On the other hand, in the Northeast, small building stock tends to have multiple stories, gables, steep pitches, old structures that pose problems with snow load, service equipment that needs upgrading, etc. Managing this kind of variation poses significant engineering and logistical challenges. I could spend hours telling you all sorts of fucked up stories about individual projects if you want a flavor of it. I suggest you talk to installers in different parts of the country and find out how the different kinds of building stock impact engineering and labor costs, because it can considerable. How do you speed up installation? Solutions are going to be regional and technological. Hand-waving answers here are a sign that you've haven't spent much time in the field.

3) The worst problem in our permitting & engineering regime for PV right now is rapid shutdown. They need to kick Bill Brooks off NEC CMP-4 and stop listening to the fire fighter's lobby; the PV industry needs a new direction on that committee. If you want to criticize stupid American regulatory burdens on PV construction, start with that. For ESSs, I think the UL9540 listing process is too equipment-specific, and some of the siting and hazard mitigation analysis regulations in NFPA 1 and the IFC could be relaxed. If you don’t know what I’m referring to, I suggest you spend more time learning about how the industry works here before writing about it, as your critique then would have relevance.

4) Most jurisdictions have a “quality certification” process for installers — it’s called an electrical license. The licensing scheme varies by state (CA, for instance, has a specialized PV license, C/46), but the intent of these licenses is to set a bar for competency in the trades. Some states (MA and NH for example) put onerous burdens on worker certification and this drives up costs, but many don’t. This is a battle to be fought with state electrical boards and state contracting regulators, if local rules are dysfunctional.

5) I’ve worked in a number of jurisdictions and I’ve never had to do a “pre-inspection” on a PV system. In fact, I’ve never once heard that term used. Some AHJs want rough inspections when you’re doing indoor wiring on new construction, so they can see what is behind the walls. This rarely applies to PV systems. I’d like to know how many jurisdictions have a “pre-inspection” requirement, and which ones. Jurisdictions where I’ve worked that separate building and electrical permits don’t usually have an in-person building inspection. The electrical inspection is the main inspection, and then you may have to file an affidavit for the building inspector from the structural engineer who signed off on the job when you submitted the permit. This mostly has to do with snow loads in northern states or hurricanes in the SE, something that isn't a much of a factor in Australia. Larger systems may have a utility witness test that requires the contractor to show up, but this has to do with interconnection, not with construction permitting.

6) Most of the big electrical supply houses have gotten into the PV equipment distribution game for small to mid size projects. In New England, there are four or five local supply chains I could call tomorrow and equipment would be dropped shipped within a week, for no shipping cost in the big metro areas. I don't know what their markup is, but I can't imagine it is much different than the markup for other kinds of electrical equipment. Large developers often work directly with PV module manufacturers and inverter companies and ESS companies.

7) For anything larger than ~1MW, the US has a significant transformer shortage, and that would be the supply chain problem that probably needs the most attention industry-wide. Specifying and securing a transformer is often the long tent-pole item for mobilization once the interconnection is sorted out.

8) The US has a problem with ESS maintenance and warranties not being easy to coordinate and execute, because legal concepts haven’t been well adapted to the technological reality of batteries, and the SCADA side of the industry needs to mature. I’m not sure how many ESS integrators are going to have staying power either, so there could be a rash of orphaned ESSs out there in the next decade. The framework for ESS maintenance and warranties should be more standardized and that's something the industry could do with internal coordination.

9) I think a fair amount of acquisition cost is tied to financing. Having to finance smaller systems means that developers and installation companies have an extra hoop to jump through, and many prospective clients will be asking for proposals that don’t go anywhere because they weren't sure if the PV system makes financial sense. The variety of building construction adds to the uncertainty (how do I know if my house is a good PV site?). This creates a lot of churn, and it is churn that is costly. Have you spent time talking to sales people here and figuring out how they can sell more effectively? If you have good ideas about how to reduce churn, you could make a killing as sales consultant in the US, and bring down those acquisition costs.

10) As far as liability goes: what are your proposals to reform state-regulated insurance markets and the legal practices that grow out these markets? Remember that these markets are responding not just to the need to build PV on buildings, but to all kinds of construction work happening in each of the 50 states plus DC.

11) I’ve never supported the tariffs on RE equipment, but I am concerned now that if the US and its allies don’t have a supply chain for panels, inverters, transformers, etc. for national security reasons. What happens if China invades Taiwan in three or four years and the escalation of that conflict shuts down access to the usual volume of goods produced in the western Pacific? I really hate (everything) the Trump Administration is doing, but the IRA has been spurring more development of manufacturing capacity in the US and among our allies. If we can get through the next decade without China going to war, then I’m all for 0% tariffs for the rest of time.

12) Interconnection here sucks, but, again, for rooftop systems, that’s a fight that has to play out at each state-jurisdictional PUC. If you want to understand the state of play across the country, talk to the folks at IREC about what might be constructive (https://irecusa.org).

In general, I’ve noticed that people writing about this in the media don’t take the time to talk to practitioners, and I think it creates a significant gap in the discourse. I suggest the next time you write about this, you spend more time getting to know the subject.

This is great! One interesting thing about the 10,000 jurisdictions is that any US state could solve this permitting and regulation problem for itself and lead the way. Florida has about the same population as Australia. California has around twice that much. State governments are smaller than the Australian national government, but the state’s economy and people have the resources to do the same thing Australia did.